Retelling ‘The Other Story’ – or What Now?

I want to lead an interpretive tour of an exhibition that closed nearly thirty years ago: ‘The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain’.1 Although vociferously dismissed by certain prominent art-critics at the time,2 the show has increasingly been hailed as a landmark initiative,3 long after the opportunity to visit has passed. My ensuing intention is to reconvene, in some senses, a public for ‘The Other Story’: to invite a walk round the exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London, where it opened in 1989, attentive to its selection and distribution of artworks.4 At the same time, I will develop arguments that are informed by critical hindsight and address a current conjuncture for art without necessarily speaking only to practice within a UK context.

To date, the legacy of ‘The Other Story’ has perhaps been most marked in the field of museum acquisitions, with Tate in particular moving belatedly to acknowledge the ethnic diversity of artists in the country and leaning on the show’s inclusions. 5 Of the twenty-four artists represented, fourteen have subsequently entered Tate’s collections.6 Indeed for eleven of these artists, particular works selected for the 1989–90 exhibition, or versions of these works, have been specifically acquired by Tate.7 Of course, this is far from conclusive and we would need to review the display circumstances for this art – and its discursive articulation more broadly – before entry into British art history could be reasonably asserted. However, my concern here is less with national canons and individual contributions; more with the constellations of artworks in ‘The Other Story’ and what they might suggest to us, with insights for practice today.

In the exhibition tour that follows, I will treat the Hayward Gallery’s two floors differently: obedient but brisk with the curatorial narration downstairs, while straying from this upstairs. And this will lead to different inflections. Downstairs, I will suggest we find a traditional European regime for understanding the art of one’s time: tracing historical trajectories and flows, to position recent art as the latest in chronologically developing trends, with sculptural and painterly modernism giving the formal measure or musical metre. Upstairs, where I will spend more time, the curatorial parcours will be followed but its conceptual framework abandoned. Instead, relationships between artworks will be traced in order to answer the following question: given an auratic mode of operation for this art,8 how does it characterise or further the project of anti-imperialism?

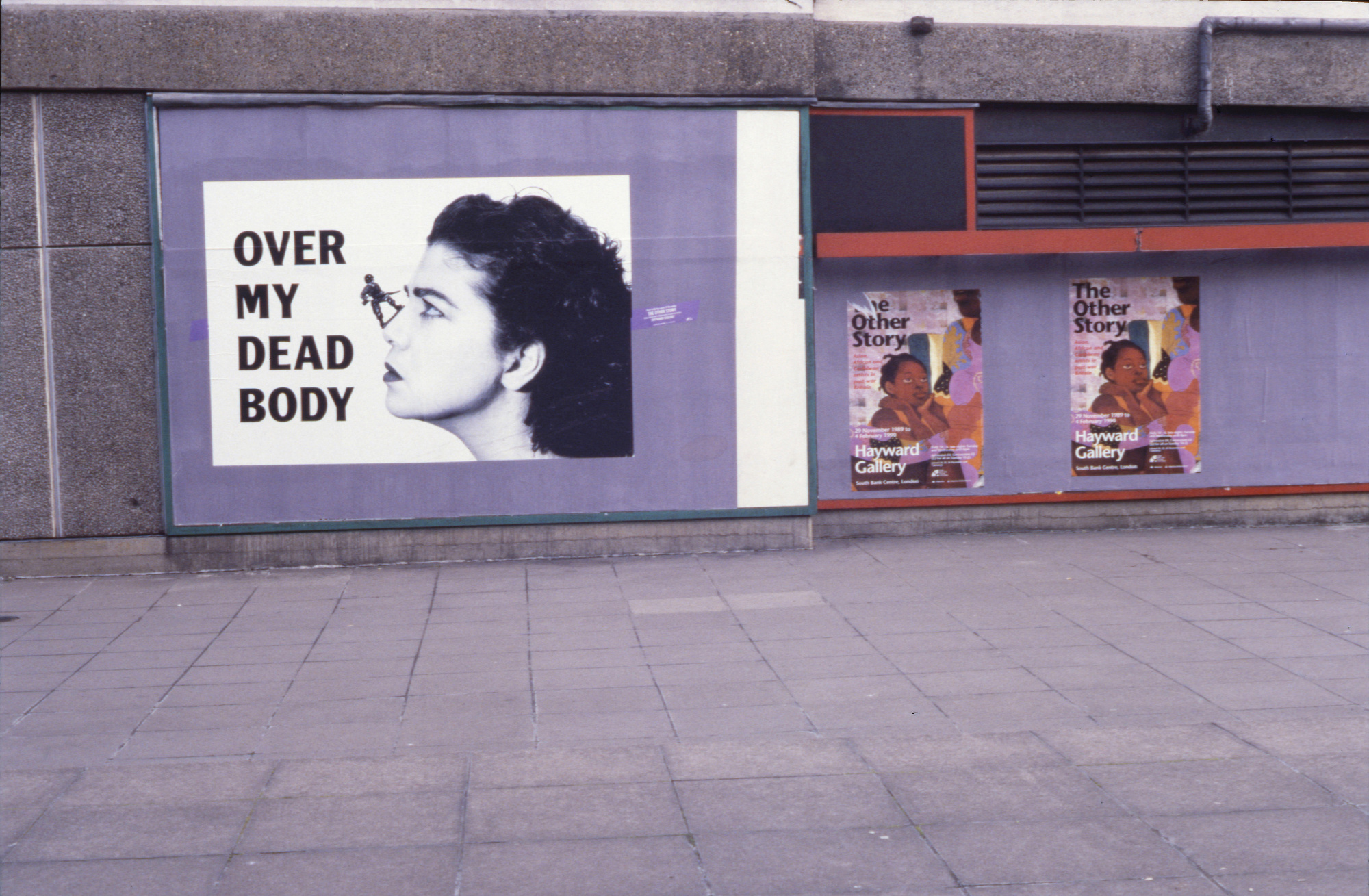

The tour starts just outside the Hayward Gallery, where it is worth reflecting on the institutional context and exhibitionary complex that was at work around and throughout ‘The Other Story’. The Hayward’s Brutalist architectural bulk proclaims a proud historical British modernism, and resonates in particular as the hold for the opening section of the show, which was titled ‘In the Citadel of Modernism’. As a part of the Southbank Centre, the Gallery’s origins date back to the 1951 Festival of Britain: the state-led celebration of national arts, science, industry and design, which marked the centenary of the Great Exhibition. If, as analysed by Tony Bennett, the Great Exhibition of 1851 played a key role in ‘the formation of a new public and its inscription in new relations of power and knowledge’ in Britain,9 then ‘The Other Story’ in 1989–90 arguably transformed not those relations of power as such, but at least the content of the knowledge being transferred.

From its opening in 1968, up until 1986, the Hayward Gallery’s programming was managed by the Arts Council of Great Britain. The independent curator of the ‘The Other Story’, artist Rasheed Araeen, first proposed his project to this institution in 1978.10 In that initial letter he addressed Andrew Dempsey, who would ultimately assume the role of in-house exhibition organiser, working in dialogue with Araeen to develop the show for the Hayward and its ensuing UK tour.11 The period of gestation, from first pitch and its rejection to final acceptance and implementation, plays out against the backdrop of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in the UK and anti-racist uprisings across the country. Increasing ideological association with the US dominated internationalist cultural discourse of the period and, at the same time, the Black Arts Movement within Britain was managing to gain some traction. 12

Paying attention to the large red banner that advertises ‘The Other Story’ on the side of the Hayward Gallery at the time of the show, discord is perhaps discernible between the external curator and the team working within the institution. Araeen, in the exhibition catalogue and wall-texts, refers to the participating artists as ‘Afro-Asian’, whereas on the promotional banner, presumably institutionally drafted, those represented are described as ‘Asian, African and Caribbean’. The latter terminology, presumably adopted with the aim of marketing clarity, seems to hold out for specificity as regards place of birth or heritage,13 rather than more loosely suggesting diasporic cultural identification within a British context at the time. It dissipates the politicised loading of the hyphenated connectivity in ‘Afro-Asian’, disbanding the solidarity ventured.14

1.

The first and largest section of the ‘The Other Story’, entitled ‘In the Citadel of Modernism’, gathered the earliest work in the show but also – for the vast majority of artists here represented (all except Ronald Moody, who died in 1984) – also contributions on into the 1980s. In other words, modern art was presented as avowedly ongoing at this time. And it was presented as the privilege of male artists: no women were included.15 Arguably renewed in its post-War emanation from the US, a modernist commitment to medium specificity was evident – with sculpture, and especially painting, allowed dominance. The two participating sculptors represented different generations and bracketed this first section, with Moody opening the first half, titled ‘Humanism and Figuration’, and Avtarjeet Dhanjal concluding the second half, titled ‘Towards a New Abstraction’. Following the curatorial parcours through the gallery space, after the winding path of figuration a corner was turned to reveal a grand boulevard sweep of abstraction.

In this opening section of the show, art may be understood in its classical or most orthodox modernist strands or tributaries – abstract and figurative, sculptural and painterly – and the overall orchestration was firmly chronological. Each artist got their own stretch or enclosure of wall or floor space but their sequencing, as individual bodies of work, steadily progressed through a linear trajectory of time. So, within the figurative section, Moody (works 1936–69) was followed by Ivan Peries (works 1938–87), Francis Newton Souza (works 1949–87) and Avinash Chandra (works 1958–89), in that order. Picking up from Chandra, Aubrey Williams (works 1963–85) represented the transition to abstraction, which then developed in a sequence that went: Ahmed Parvez (works 1959–78), Frank Bowling (1959–89), Balraj Khanna (works 1972–89) and Dhanjal (works 1979–86). As such, Khanna’s paintings and Dhanjal’s sculptures, at the concluding point, were operative as both culmination and continuation of modernism.

2.

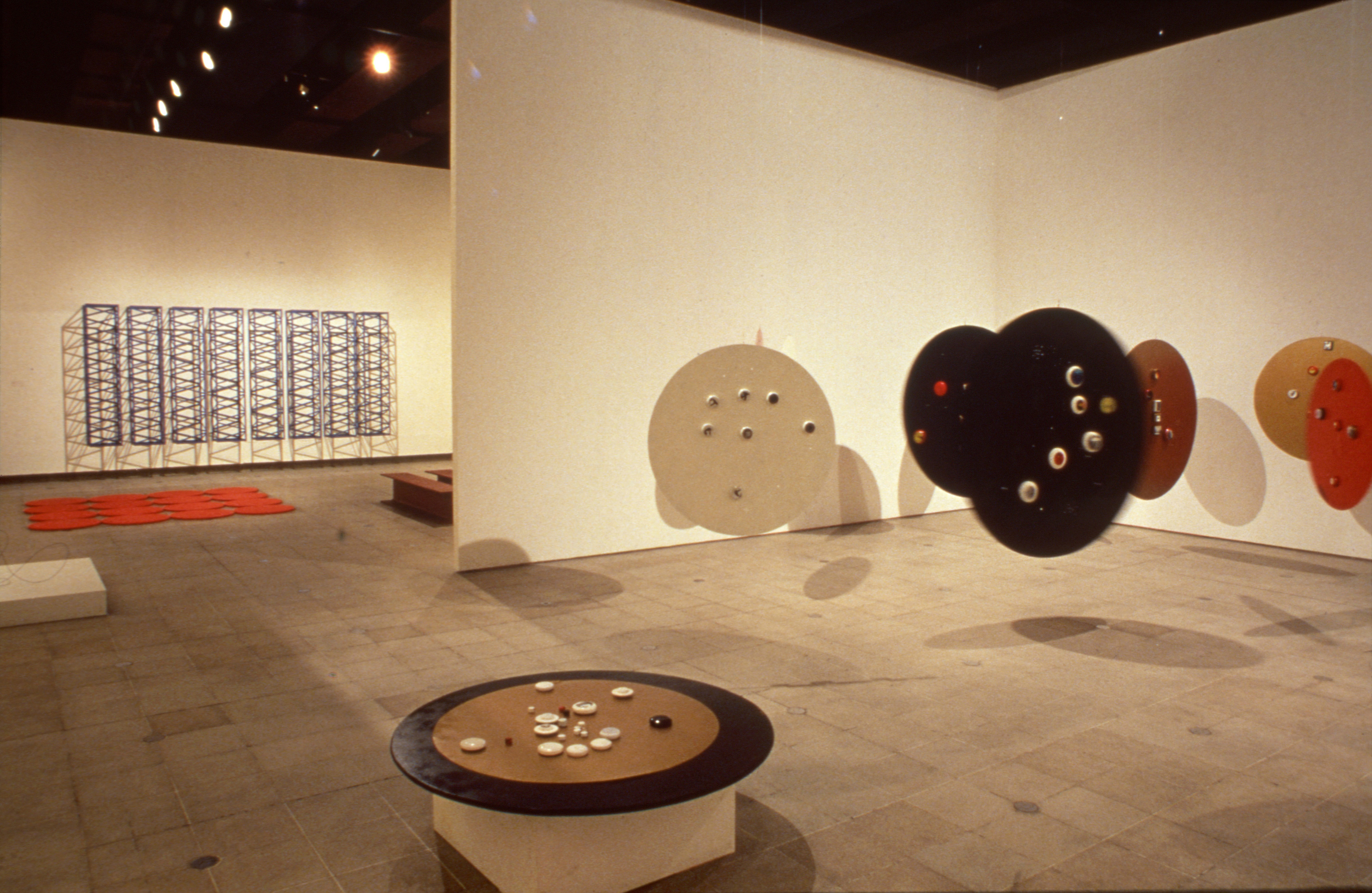

The second section of the exhibition, ‘Taking the Bull by the Horns’, reflected painterly and sculptural modernism as wrestled with in the 1960s. It represents a fork off from the mainstream, into a waterfall and plunge-pool, perhaps, of aleatory, performative and participatory experimentation that troubled medium specificity. Just four artists were included and again all were male. In fact early installation plans for the exhibition suggest that Kim Lim had been hoped to play a part here in the exhibition, but – as Araeen notes in the catalogue – she was one of five artists who declined the invitation to participate.16

The practice gathered in this section was anchored in the 1960s but its selection may be read as a concerted critique of the neo-expressionism that, in painting in particular, was widely celebrated in the 1980s. In this light, the ashes of numerous burnt paintings by Iqbal Geoffrey, the auto-ejaculatory foam of David Medalla’s Cloud Canyons (or Bubble Machine) as first made in the early 1960s and the wind-scattered discs of Araeen’s own Chakras (1969–70) collectively mock the gravitas of subjective expression as reasserted through certain art of the 1980s. Likewise, Medalla’s recreation of A Stitch in Time (1968) along with Li Yuan-chia’s adjacent magnetic Toys (from 1967) invite visitor participation and thus playfully form themselves through others’ self-expression. A critique of neo-expressionism is perhaps offered explicitly in Araeen’s Green Painting (1985–86), which concludes this section of the exhibition. Here photographs of spilled blood on rough ground offer not a revisitation of abstract expressionism but a biting parody.17

3.

In the original layouts for ‘The Other Story’, drafted before the installation was worked out in situ, the parcours paused after the sections I have now briefly considered, inviting visitors to climb the stairs in order to explore the next and concluding two sections of the show. In the final hang, however, the opening to the third section, ‘Confronting the System’, was brought downstairs, into direct relation with ‘Taking the Bull by the Horns’. Specifically, we find contributions by Gavin Jantjes and Mona Hatoum: framed prints and canvas-based works by Jantjes (1974–89) take up where Araeen’s Green Painting left off, snaking the booth constructed for the presentation of three video works by Hatoum (1983–88).

Following the flows coursing through the show so far, the work of Jantjes and Hatoum here form paired rivulets that each develop a current in the work of Araeen in particular, which I will give full force upstairs: the political project of challenging cultural dominion.18 Here, downstairs, a baton is passed from those ‘Taking the Bull by the Horns’ in the 1960s and 70s and given to those starting out, in the 1970s and 80s, with the aim of ‘Confronting the System’. As such, the work of Jantjes and Hatoum chimes with the terminus for the earlier branch of the show, offering a parallel to Khanna’s paintings and Dhanjal’s sculptures as the latest developments ‘In the Citadel of Modernism’. And, as such, we conclude the traditional regime for understanding recent art practice, as presented in the downstairs hang of ‘The Other Story’: we have now trailed the historical flow-diagram – charted over time – that was drawn curatorially.

4.

At the top of the rear steps leading into the upstairs galleries, visitors were expected to turn right – into a continuation of the section titled ‘Confronting the System’. And from there they would have entered the final section, ‘Recovering Cultural Metaphors’, which wound back round to the top of the steps and then on into the final gallery. While adopting this same path, I propose to understand this top floor differently, pursuing the commonality in the two thematic strands proposed, rather than endorsing their divergence or parallelism. In sum, this means exploring a nexus of anti-imperialism upstairs and rejecting the teleological narratives of modernism instigated downstairs.

This is not the reading of the show upstairs that I first made when studying the catalogue and installation shots. I spent a long time elaborating the categorical distinctions that were drawn – on the page and in the galleries – between work seen as ‘Confronting the System’ and that seen as ‘Recovering Cultural Metaphors’. My initial suggestion was that, looking back, what we might perceive was a late 1980s division between ‘contemporary’ art, on the one hand (in the name of ‘Confronting the System’), and ‘postmodern’ art, on the other (as dubbed ‘Recovering Cultural Metaphors).19 Here I was pushing for contemporary art to be postconceptual – both art historically, after Jean Fisher’s reappraisal of the show in 2009,20 and ontologically, after Peter Osborne’s philosophical proposal of 2013 21 – and, simultaneously, I sought to invigorate a strain of postmodernism in relation to art by insisting on strict postcolonial drivers. 22 However, this approach did not seem to open up a critical repertoire that was especially useful at the present conjuncture for artistic practice. As an alternative, I thought I might explore the 1980s dialectic between ‘Black art’ (naming work by those ‘Confronting the System’) and ‘Black aesthetics’ (grouping artistic practice by those ‘Recovering Cultural Metaphors’). 23 However, this proved another unsatisfactory polarity, which risked reducing complex matters to simply the political vs the formal, for example, or the conceptual vs the affective. Ultimately, I have been inspired by the work as displayed upstairs to abandon any proffered or extrapolated dichotomies and to see the disparate contributions made both more particularly, in their own terms, and more concertedly, all together.

Here, in general, modern art as historically anchored in nineteenth-century Paris – and undiverted by the gathering chorus of performative, conceptual, process-based and event-based artistic experiments around the world in the 1950s–80s – continues with the production of auratic objects: unique and authentic pictures and sculptures to be preserved for ritual contemplation, to stimulate individual enlightenment. And yet, at the same time, the modernism at work here is resolutely anti-imperial: it refuses to privilege the gaze from within the colonial ‘citadel’; it pluralises and entangles its geopolitical publics. While commanding aesthetic appreciation – as a meditative engagement anchored in and conditioned by the museological, white-walled and no-touching gallery tradition (as re-entrenched in the 1980s) – it addresses more than one cultural audience. It articulates intertwined cultural histories and, whether harmonising these or exposing the antagonisms, there is discourse between them.

Certainly, this is an interpretative framework we could easily activate for much of the work downstairs at the Hayward Gallery too. However, the curatorial vectors there (the extended sweeps and clean thrusts) resist this rather different, more assemblage-style reading, which is easier to discern upstairs – albeit by accident of the emergent installation plan, which saw the sharing of the penultimate gallery by parts of the exhibition’s two final chapters. Even if only inadvertently, the view into this gallery on reaching the top of the stairs, where visitors found three alternative paths – lured by work to the left, right or straight ahead, without curatorial signposting – suggests more openness and cross-pollination.

5.

Following Keith Piper’s work, right, and heading towards Eddie Chambers’s work, beyond, visitors entered a space in which these two artists were set into conversation. Longstanding collaborators on conferences, exhibitions and publications by this point in the 1980s, this was an obvious pairing but it broke productively with the artistic separations along linear paths in the galleries below.

Both Piper and Chambers referenced banners or flags in their contributions,24 mining the semiotics of political protests and parades – bringing echoes of these alternative forms of public address into the otherwise hushed painterly and sculptural forum of the white cube. Moreover, each artist was also represented by work that, eluding the gallery context, had previously circulated on the printed page via Third Text, the art journal founded by Araeen in 1987. 25 Nevertheless, all works by both artists at the Hayward were carefully hung according to exhibitionary norms – about a strict midline, with regular breathing space between them – inviting the one-on-one public communion between work and gallery-visitor as encouraged by convention. As such, they held back from critiquing the display context and instead worked at ‘confronting the [museological] system’ within its own terms. Of course this is a much noted paradox of ‘The Other Story’, which is not limited to these artists but overarching, given that the show sought sanction by the very establishment it otherwise sought to put into question on the basis of racist neglect. The explicit anti-imperialism of the work shown by Piper and Chambers exposed something of the viciousness of such predicaments.

I want to spend a moment with two works by Chambers that dealt with British racism of the time through astute reference to the Union Jack, since these were particularly effective in the Hayward Gallery as a setting, given its flagship national status for art. In the four collages constituting Destruction of the National Front (1979–80), a swastika cut out of the British flag, as set upon a black background, is progressively torn apart.26 The specific cultural reference for this work was a poster produced by the Anti-Nazi League that is dominated by a pixelated image of a bawling Adolf Hitler, presented under the headline ‘The National Front is a Nazi Front’, with a small but alarming banner conjoining the Union Jack and the Swastika born at the centre of a sea of marching bodies that fills the rest of the page.27 However, Chambers’s work is equally indebted to the rip-and-paste punk aesthetic developed as an anarchic strand of British identity in pop music at the time. In both ways, the work’s address is to a conflicted mass audience rather than restricting itself to a traditionally rarified gallery-going public.

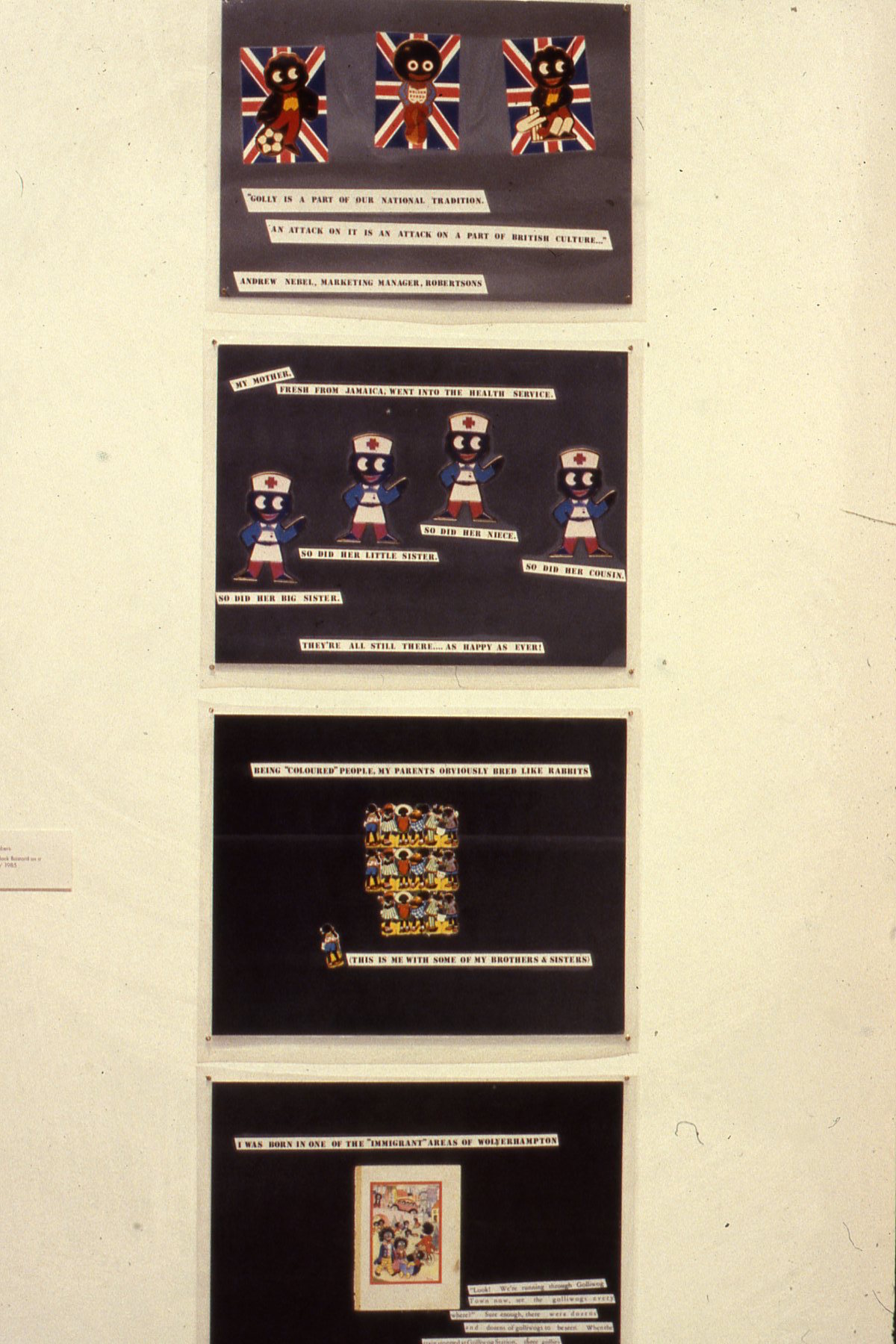

In the four panels at the Hayward sampled from his touring exhibition ‘The Black Bastard as a Cultural Icon’ (1985),28 Chambers again used collage but here drew on his extensive collection of British cultural artifacts mobilising so-called ‘golliwogs’, the racially offensive cartoon doll with a black face and fuzzy hair. The Union Jack features in triplicate in the first of these panels, as a backdrop for photographs of three golliwog badges issued by Robertson’s jam as part of a prolonged branding and advertising strategy only abandoned in 2002. The company’s marketing manager is quoted on this panel as saying ‘Golly is a part of our national tradition. An attack on it is an attack on a part of British culture.’ The ‘our’ in this context is brought out carefully in subsequent panels, where the personalisation of using the possessive term ‘my’, in connection with being born British with African heritage, merges troublingly with racial stereotyping rather than bringing out lived particularity. Here again, as in Destruction of the National Front, Chambers addresses the British public at large, in its ethnic diversity, whether or not all cross the threshold of the Hayward Gallery with equal ease.

The juxtaposition of found image and text, to suggestive political effect, resonates with Barbara Kruger’s contemporaneous work in the US, but there is more of an archival feel to the work by Chambers: his aesthetic recalls a personal scrapbook circulating by post, rather than the hijacking of a corporate advertising campaign. The research-based accumulation of materials, which Chambers makes present and narrates, asks for a different sort of engagement.

6.

A solo display of Lubaina Himid’s work drew visitors out of the space shared by Piper and Chambers. Here again there were formal hints at the gallery setting not having exclusive dominion as a public forum for visual culture, with an unstretched canvas and propped figurative placards pointing towards street carnival as well as political protest. And, here again, work sampled from earlier exhibitions was included and gained distinct significance in the new context. In particular, Himid reworked her artistic contribution to the group show she curated for a corridor space at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 1985: ‘The Thin Black Line’.29 Three Women at the Fountain was remade as a work on canvas for the Hayward, (presumably) having been scraped off the walls and painted over in the ICA corridor where it was initially installed. The Carrot Piece, shown alongside, was more transportable: formed from a pair of larger-than-life figurative cut-outs, resting between floor and wall, they might have just stepped out of the previous exhibition context.

The left-hand figure in The Carrot Piece is a pink-skinned unicyclist, a dapper clown who – flushed of face and thrown back in the saddle – dangles the proverbial carrot on an attenuated stick. There it is eyed with suspicion by the backward glance of the right-hand figure, who is brown skinned, wears a red dress and, with hands full, walks resolutely ahead. Seen as a satire on the (White and patriarchal) art establishment and its compromised offer to marginalised (Black and female) artists, the eloquence of this work within ‘The Other Story’ builds on its previous presence within ‘The Thin Black Line’. In the earlier exhibition, the speeding arrows driving round the monocycle’s wheels could be seen as the pressures the Greater London Council (GLC) were exerting on institutions at the time to reflect Britain’s ethnic diversity in their programmes – with the work thereby offering a commentary on the genesis of Himid’s curatorial project in the ICA corridor.30 Here at the Hayward, four years later, the GLC had been dissolved by Thatcher’s government and responsibility for support of so-called ‘ethnic minority arts’ had transferred to the Arts Council of Great Britain, which both enabled ‘The Other Story’ to take place and muddled Araeen’s distinct agenda. As such, The Carrot Piece flagged both the opportunities and limitations of Araeen’s and the Hayward’s offer, questioning the seriousness of the proposition to rewrite British art history without imperial prejudice.

Looking back, this goes hand-in-hand with the work shown alongside, which commodified itself for assimilation and yet has since been lost: Three Women at the Fountain has once again, although not deliberately painted over this time, physically disappeared; scored from all debate except through minimal documentary photographs. In ‘The Thin Black Line’, this work knocked back the ICA’s white walls and claimed the institutional space for Black women, supporting their imposed need to ‘fight’ and to ‘fight on’ (to quote prominent collaged elements).31 Reinterpreted by Himid for the Hayward, on stretched canvas and without text, the work may seem docile in its conforming to the pictorial production-mode that is time-honoured within Europe; however, its reference to a specific painting by Pablo Picasso (of almost the same title and about the same size) is thereby brought out. Here it develops an earlier piece by Himid shown on the perpendicular wall, Freedom and Change (1984), which reworks (with more formal liberty, greater pictorial escapism) another Picasso painting from the same period in his career. In both, he incorporated into his figuration a monumental bulk drawn from ancient Greek and Roman cultural confidence, as if to pacify the European cultural crisis in the wake of World War I. Himid introduces brown hues for skin and modern female dress, in the place of pinker skin hues and vaguely classical garb that exposes naked breasts. In this way she invites reinterpretation by established Hayward audiences – for instance, those who visited the Picasso blockbuster at the beginning of the decade – and she also addresses those who might not recognise the art historical references and yet could still appreciate the respectively reflective and joyous images of solidarity with Black women, here and now. Her anti-imperialism is not combative except by opening to question the lusty White male gaze assumed by much traditional art history.

Another London exhibition that perhaps hovers behind Three Women at the Fountain and Freedom and Change, which took place the same year as ‘Picasso’s Picasso’ at the Hayward, is ‘A New Spirit in Painting’ (1981).32 This presaged a reinvigoration of works on canvas in the 1980s, while managing not to include any female artists among its 38 contributors. The curatorial statement in the exhibition catalogue avows a commitment to ‘common threads which cross national boundaries’;33 however, the drive was apparently to draw on UK practice and that from Europe more broadly in order to diversify, even dilute, the ongoing US command of art of the time. Imperial claims upon painting as a White profession go unchecked, with no artists who might identify as ‘Afro-Asian’ included.

7.

Himid’s work shares a wall, across a doorway, with the paintings of Uzo Egonu, which are otherwise shown in relation to the pictures (prints and paintings) of Anwar Jalal Shemza and sculptures of Donald Locke. Her cut figures bring out the graphically defined shapeliness of the forms produced by this trio of older artists born in three different continents. And it is notable that they are presented here all together, as a possible field or pool of practice for consideration. It is as if their quietly anti-imperial takes on modernism demand a rejection of the linear master narratives of colonial art-history writing, as dutifully followed downstairs.

Abstraction and figuration are productively crossed and exchanged in these works, with the scene-setting in Egonu’s, on one pair of walls (oil paintings 1964–88), bringing out landscape in the patterning of Shemza’s on the pair of walls opposite (works 1958–84) and still life in Locke’s sculptures between them (works 1970–89). Distinct positions on the urban meeting the rural, or the geometric meeting the organic, are elucidated between them.

In the work of each artist, there is formal experimentation that is admirable within the established painterly and sculptural trajectories of European and North American modernism, yet all the artists simultaneously channel and engage formal practices rooted beyond these world regions. And this may be distinguished from Picasso drawing on African figurative work, or Jackson Pollock emulating something of Navajo sand painting, because there is cultural dialogue rather than unidirectional appropriation – and plural audiences are consequently addressed.

8.

Around a corner constructed from temporary walls, Locke gets an additional solo presentation. Here the anchoring contribution is Trophies of Empire (1972–74), which formally unites the company it keeps on both walls and floor. This work addresses imperialism (and indeed, more specifically, colonialism) with such arch poise and devastating stillness that I am keen to emphasise again that the ‘anti’, which I am working with as a prefix for work in these upstairs spaces, does not necessarily imply an opposition that is aggressive. And yet, as here, with succinct but overwhelming pathos, it can still feel powerfully articulate.

Between Locke’s sculptural work and Kumiko Shimizu’s, which followed at the Hayward Gallery, another British exhibition from 1981 comes to mind as a comparative context. ‘Objects and Sculpture’ united the recent work of eight young artists working in Britain and included Anish Kapoor, who would later decline to take part in ‘The Other Story’.34 Without presenting a historical backstory, as did ‘A New Spirit in Painting’, this show was nevertheless alike in presaging a triumphant return to medium-specific formalism, confidently evacuated of political critique. Otherwise, the curatorial description of what characterises the work brought together offers a decent description of the sculptures of Locke and Shimizu as presented inside the Hayward:

The work appears to be decidedly ‘impure’ in utilising either base or rejected materials and with the frequent incorporation of actual real objects or images of real objects. It has strong human connotations, either in its scale, in its tactile qualities, in its images or through the evident ways in which it was made.35

My point here is not that either Locke or Shimizu should have been included in this earlier show. Shimizu was still studying art in 1981 and Locke, who was a generation older, had already left the UK for the US by that point. However, this synopsis of a strand of sculptural practice that would come to dominate 1980s Britain – notably through commercial exposure at and promotion by the Lisson Gallery36 – offers an interesting ground on which to examine related practice included in ‘The Other Story’.

As described for the art assembled in ‘Objects and Sculpture’, Locke’s Trophies of Empire and contemporaneous Plantation Series (as sampled at the Hayward) ‘seem to refer both to objects in the world, and to sculpture given some status as a category of special objects separated from the world’.37 However, the strength of Locke’s work lies precisely in questioning the givenness of one’s world and in gently introducing the profound threat of imperial power as regards worldly disruption if not desolation – while elaborating something of the complex ensuing legacies. The social engagement that fed Trophies of Empire in particular also seems to mark an important distinction from the sculptural work that would become celebrated in Britain in the following decade. Locke has written that the sculptural forms ‘in the bottom row of the cabinet, except the one in the middle, were made by boys at Hammersmith House, a remand home in Shepherd’s Bush Road, where I was teaching pottery in 1972–3’. 38 The contribution of these marginalised London youths to the work anchor it in a plurality of entangled worlds, rather than allowing for the existence of ‘the’ one.

Shimizu’s contribution in the upper galleries of the Hayward was dominated by an array of scavenged hardware – discarded tools, pots and pans, for instance – all boldly painted and scattered over a corridor wall. This offered a tamed taster of a work that covered the exterior of the building, where it otherwise developed an anti-imperial thrust with considerable eloquence (as I will come on to address). Here, inside the galleries, the work resonated quite simply with the sculptural practice of her generation in Britain. To pick up on the curatorial preface to ‘Objects and Sculpture’, Shimizu shares the specified interest in eclecticism and anarchic humour, while achieving her own particular ‘impurity’ of practice by messing with the modernist medium-specificity that was crucial in the US – and echoed in 1980s Britain – by adding painted pictorialism to Duchampian found sculptural form. Nevertheless, the framed photographs that accompanied her gallery display – documenting both the installation of her work on the Hayward Gallery’s exterior and four earlier and similar urban projects – also point to other concerns. They reveal the process-based involvement of others in the production of her work and a commitment, contra ‘Objects and Sculpture’, to its environmental situation.

9.

Crossing ‘The Other Story’ upstairs, Shimizu’s work channelled Keith Piper’s to Sonia Boyce’s, with a detour offered via Saleem Arif’s. It is difficult to find an anti-imperial strand in the latter’s exhibited paintings (1975–89), which productively prompt a return to the contemporary and earlier work of Egonu and Shemza, as shown in the previous gallery, and to Himid’s, in the one before that. By comparison, Arif’s beautiful work has a fairy-tale completeness – an overall picaresque positivity – which seems more concerned with a universalising address rather than one specifically transcultural. I perceive an ease of worldliness here, which verges on divine or mythic transcendentalism that distracts from the realities of cultural strife, obscuring the terms of its negotiation in particular contexts.

Not unlike Himid in some of her work, Arif engages illustration, while simultaneously rejecting certain painterly conventions such as the stretched canvas with its solid rectangular entirety. By comparison, Boyce’s work, opposite,39 returns us four-square to the European art historical tradition and – where Egonu takes up still life and landscape and Shemza abstraction – her focus is firmly on the genre of history painting. Only it isn’t paint that predominates in her pictures, but rather pastel, crayon, charcoal and collage. In both Missionary Position I (1985) and Lay Back, Keep Quiet and Think What Made Britain So Great (1986), for example, Boyce deals with the history and legacy of colonialism head on – tackling issues of religion, race, feminism and murder with taut precision. She unites distinct visual traditions, traces and symbols to juxtapose their geopolitical underpinnings, articulating some of the traumatic complex burdens bestowed by an imperial past.

10.

To conclude my tour of ‘The Other Story’, I want to pause in front of Shimizu’s work as installed on the outside of the building, where it would have been seen even by those not choosing to enter for the show. High up and encroaching onto the terraces, her Project for the Hayward Gallery (1989) amplified the array of scavenged and painted hardware that was shown inside, on the white walls. Here, outside, found objects – not just pots and pans now but also larger items: car parts, a wheelbarrow and a lavatory, for instance – gained vividly coloured coats and swarmed the concrete exterior. An architectural fungus took a temporary hold on this London landmark.

Far from the apolitical spectacle, pastiche and degraded historicism gathering steam under the label of ‘postmodernism’ in certain circles at the time, Shimizu’s Project for the Hayward Gallery – seen in the context of ‘The Other Story’ – insistently acknowledges the failings of the modernist project while working with the cultural vestiges. The work infused the flotsam and jetsam of British life after the Industrial Revolution – and specifically of London as its urban hub – with teeming lyrical realism and chaotic urban environmentalism. Engaging the Brutalist building as a vestige of European overconfidence, perhaps, the work antiquated its vast – shipwrecked? – hulk with a panoply of thriving barnacles.40

Distinct from the majority of the work within the Hayward Gallery at the time – and developing the avant-gardism of the performative and participatory work buried at its heart – Shimizu’s installation was irreverently non-auratic: messy, non-unified, socially intrusive and entangling. It resisted solitary contemplation by exceeding any single perspective and by occupying a location typically thronged with people. More specifically, it inscribed the building with humble but bold personal narratives that – through the sheer familiarity of the objects co-opted – addressed the passing crowds of London’s South Bank as a ‘we’ who must imbricate ‘our’ different relationships to British cultural heritage.

11.

To the extent that it is possible today – over a quarter of a century after the close of ‘The Other Story’ – I have now walked a route through the exhibition. It is clearly possible to see the show as a simple redress to all the books and exhibitions that told (or indeed continue to tell) the story of British art in the twentieth century as an exclusively White artistic affair – and its significance in this regard cannot be underestimated. However, its particular interest for me now regards a sharpening of how we might approach recent art practice as displayed today. From wandering the upstairs galleries, in particular, I have taken anti-imperialism as a banner under which productive heuristics for art’s discussion may be ventured. I have been encouraged to insist on art’s historical consciousness while resisting any teleological modernist art history. The show has reconciled me to the ongoing auratic functionality of art, while simultaneously encouraging my interest in its concurrent ethical capacity for socio-political entanglement.